Disaster Recovery Ignored: How CME Let a ‘Cooling Glitch’ Freeze Global Markets

How a ‘cooling glitch’ at CyrusOne knocked CME offline for nearly 10 hours—and why that should terrify you.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange CME 0.00%↑ is one of the world’s largest financial exchanges, based in Chicago, where traders buy and sell contracts tied to the future prices of commodities, foreign currencies, stock indices, energy, interest rates, and metals. It operates nearly around the clock and is the main venue for U.S. futures and options trading.

In the late evening hours of Thanksgiving 2025 — just as many Americans were likely fast asleep in a food coma — a strange series of events occurred at one of the nations most critical financial data centers servicing CME.

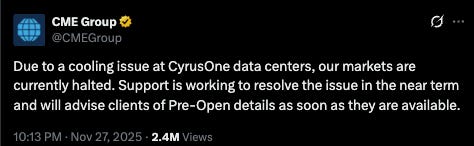

At approximately 9:00 PM (CST,UTC-6) traders were notified of a CME contracted data center “cooling issue” at the CyrusOne facility in Aurora, Illinois (roughly 1 hour from Chicago) - trading on Silver (which was near record highs) was halted in tandem with other CME operated markets.

The unprecedented outage would go on for upwards of 10 hours and was attributed to a “cooling” failure — now financial communities on the internet are rife with rumors and conspiracies regarding the true cause of the outage. I’ve uncovered via CME’s own policies that safeguards for this scenario were blatantly ignored.

This is where things get interesting as pointed out in No1’s excellent article:

In short, the banks were about to get beat, and a large whale was about to cash in on their position by demanding physical delivery of Silver. My article is intended to further investigate the “cooling” issue and not get into the exact specifics of the macro/micro economics and futures contracts. Please read No1’s article above for that.

The Odds of a “Cooling Issue”

As if a critical financial market being down for 10 hours isn’t staggering enough, lets get into the granular details.

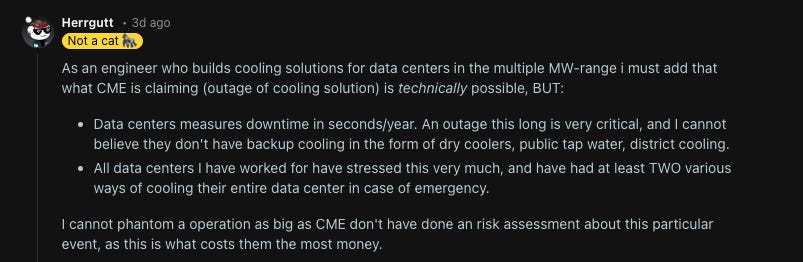

Critical financial data centers are designed with multiple independent cooling paths (N+1, 2N, or higher), hot/cold aisle management, continuous monitoring, and strict maintenance so that any single failure should not take the site down. The odds of both primary and backup cooling failing at the same time in a properly engineered Tier III–IV facility is extremely low—on the order of “one serious cooling-caused outage every several years”—but not literally zero.

To give an exact number on the odds — Tier IV data centers like CyrusOne average only 26 minutes of downtime per year (given all causes) — cooling related downtime in the datacenter industry generally represents only about 10-15% of all outages — with power issues dominating most.

CyrusOne’s Aurora facility servicing CME burned through roughly 21 years’ worth of its ‘allowed’ downtime budget in just ten hours.

An outage like this would be moderately believable and understandable if this was in the middle of a heat wave during a particularly hot Chicago summer.

—

It was a meager 28 degrees Fahrenheit outside (about −2 degrees Celsius)

Here is where it gets even more interesting —

CME failed to execute disaster plans and industry recognized resilience protocols. According to CME’s own operational-resilience plan — in the event of a data center outage at CyrusOne operations are to pivot to a backup datacenter in New York. Oddly enough CME decided not to do this as the “temporary” outage dragged on for hours.

CME also has a policy and plan outlined for this exact situation:

In scenario 1, the primary CME Group data center (CME Aurora) and redundant access node (350 E Cermak) have been forced to cease operations. All CME Group Chicago area datacenters are unavailable and customers will be re-directed to the disaster recovery facility.

Implementation of a Disaster Recovery Plan (DRP) is no easy feat and execution is gauged against a Recovery Time Objective (RTO) — which is the maximum amount of time a system is allowed to be down before pivoting to the DRP-site. — Consider the RTO a cost/benefit model and a sliding scale based on the criticality of the system — for critical financial systems the RTO is usually set very low with a general rule of no more than two hours.

CME documentation/policy states the RTO for their clearing house systems is two (2) hours:

The recovery timeframe in the event there is a disruption to the data center that houses the CME Clearing production environment will be 2 hours or less.

By conventional DR/RTO standards, a critical financial market should either recover its primary site or pivot to a DR-site within one to two hours.

Almost 10 hours of downtime is roughly five times longer than the industry standard.

Each minute past two hours in my opinion is further evidence of pure incompetence at best, and criminal level market manipulation at worst to “force majeure” demands for physical silver delivery — which as pointed out in No1’s article simply didn’t exist.

The facts are hard to ignore

Just so we’re straight — several failure points seemed to conveniently align in a perfect storm for CME:

A Tier‑IV CyrusOne data facility, servicing one of the worlds largest financial exchanges, suffers a once‑in‑decade cooling failure, on a cold Chicago night.

CyrusOne’s back-up cooling systems either failed, or were not adequately utilized.

The outage then exceeded CME’s two hour policy.

CME failed to execute their disaster recovery plan and pivot operations to a secondary data center in New York, designed for this exact scenario.

CME allowed the outage to drag on for over 10 hours all while never executing their DRP.

A lion-share of the downtime can now be directly attributed to CME and not just CyrusOne. As — CME had the need, means, and ability to execute their DRP they, however, failed to do so.

This is not what sound, resilient, and competent market looks like. And the system that just showed you how fragile it really is.